Chinese porcelain was already known in the Netherlands before 1600 thanks to trade with Portugal and the voyages of the so-called pre-companies (voorcompagnieën) to Asia, but it was a scarce and expensive product. The auctions of porcelain seized from two captured Portuguese ships, the São Tiago in 1602 in Middelburg and the Santa Catarina in 1604 in Amsterdam marked a turning point: suddenly a relatively large quantity of porcelain became available for an interested public with money to spend. Since then, Chinese, and later Japanese porcelain, has been a constant presence in the material culture of the Northern Netherlands.

The VOC

In 1602, the Dutch East India Company (Verenigde Oost-Indische Compagnie, VOC) was founded as a shareholder company, with exclusive rights to trade in Asia. Besides spices and other profitable items, porcelain was also part of the VOC’s product range. This contrasted in the Netherlands with the ubiquitous locally produced, simple pottery and elaborate majolica. Porcelain was a considerably harder substance and thus easy to clean, had a high gloss, was thinly fired, and the Chinese decorations in underglaze blue on the bright white ground were eye-catching and appealed to the imagination.

The VOC could not access China, so it bought porcelain from markets elsewhere in Asia, resulting in a highly variable supply to the Netherlands. The establishment of Batavia in Java (1619) as the Asian headquarters of the VOC and as a central transhipment point did little to change this.

Kraak porcelain

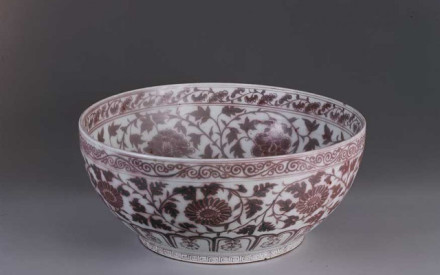

In China, porcelain was traditionally made in Jingdezhen, a ceramics centre in northern Jiangxi province. So-called Kraak porcelain had been developed especially for export since around 1570. Difficult to define, ‘Kraak’ denotes a type of porcelain that, for cost reasons, was mass-produced in an almost industrial manner in a limited number of shapes with standard dimensions that could be efficiently loaded into a ship’s hold. The decorations are almost always in underglaze cobalt blue and usually depict flowers and plants in natural settings, or birds, insects, deer and mythical creatures (fig. 1). Such representations were politically and religiously neutral, making them suitable for a wide range of clients in Asia; figural representations are therefore rarer. Border decorations on dishes are often divided into wide and narrow panels, filled with flowers, fruits or lucky symbols; decorations on bowls, pots, covered boxes, ewers and kendis are also typically divided into panels. Usually there is some kiln sand adhering to the bases of flatware and to the footrings. Special objects, made or decorated on commission after a supplied model are rare, for instance, salts and casters for a European client. The extent to which Kraak porcelain was specially made for Arab, Indian or Malay traders is unknown.

Transitional porcelain

Political and economic changes in China and the South China Sea led to a new phase in the VOC’s porcelain trade. By 1624, a settlement on Taiwan (then called Formosa) had been established as a transhipment point for the East Asian trade. Contacts with Southern China thus became easier and from 1632 orders for porcelain could be placed in Jingdezhen through Chinese traders. Besides the traditional Kraak porcelain, an entirely new type now became available, so-called Transitional porcelain. This is of a much better quality than Kraak: the body is made of superior porcelain, carefully shaped and finished, the glaze is smoother and brighter, the decorations are much more varied, include figural representations, and are intricately painted without dividing lines (fig. 2).

The rise of this type of porcelain was due to changes in production in Jingdezhen when orders from the imperial court declined and potters had to find new customers. These were mainly from China’s developing middle class, but also foreign traders, including the VOC. Consequently, much of the porcelain bought via Taiwan at the time has Chinese shapes while the decorations draw on an iconography often based on classical Chinese literature. In addition, it was now also possible to order objects with Dutch shapes that the Chinese potters were not familiar with, such as candlesticks, mustard pots, beakers, beer mugs, salts and the like (fig. 3). For these, the VOC sent along an original example made of tin, earthenware or stoneware, and if these were not available, a wooden model was made. In a few cases, the Chinese painter also copied the decoration from a European example, but Dutch customers preferred an ‘exotic’ Chinese representation on their beer mug or ewer.

The period in which this type of porcelain was supplied to the VOC lasted only briefly, from 1634 to 1647. By 1644, the Ming dynasty had been replaced by Manchu forces from the north who established the Qing dynasty (1644-1912). The wars and upheavals that followed made transporting the porcelain from Jingdezhen to ports in the south increasingly difficult, so the VOC had no alternative but to end its porcelain trade with China.

Dehua, Zhangzhou, Yixing and Longquan

During this period, the VOC’s trading activities were not only limited to Kraak and Transitional porcelain for the Netherlands and for Asian markets. There were two centres in southern Fujian province where export ceramics were also produced: Dehua and Zhangzhou. In Dehua, potters specialised in white, undecorated porcelain where the shape was accentuated by the cream-coloured, flowing glaze. It was later called blanc de Chine in Europe and is best known for the figures of Chinese deities, e.g., Guanyin, and Daoist Immortals (fig. 4). The VOC also purchased small quantities of this type prior to 1644.

The kilns in Zhangzhou manufactured sturdy porcelain or stoneware dishes, pots, covered boxes, etc., intended for intensive daily use. It was fluently painted in underglaze blue or overglaze enamel colours (combinations are very rare) with animals, flowers, sometimes figures and occasionally European or Islamic motifs (fig. 5). This type, formerly called ‘Swatow’, was not shipped to the Netherlands but played a role in the VOC’s inter-Asian trade.

Kilns in Yixing, in the eastern province of Jiangsu, also contributed to a limited extent to the VOC’s assortment for Dutch and Asian buyers. Here, hard-fired, unglazed red stoneware was the speciality, a product highly prized in China, especially in the form of teapots (fig. 6). These were also extremely popular in the Netherlands, but were so scarce that the Delft imitations caused a furore as an available alternative in the early eighteenth century.

Finally, a flourishing industry had existed for centuries in Longquan, supplying China and the whole of Southeast Asia with sturdy dishes, pots, vases, incense burners and other utensils covered with a grey-green glaze. Such ceramics were later called celadon in Europe. It remains unclear to what extent the VOC also included these ceramics in the assortment for its inter-Asian trade, but like Zhanghzou ware, it was considered too ‘coarse’ for the Dutch market.

The Hatcher Cargo

The dynastic change from the Ming to the Qing dynasty also brought an end to the export of all these types of ceramics around the middle of the seventeenth century. A wonderful example of the complexity of the international ceramic trade of the time is the cargo aboard a wrecked Chinese junk from 1643 (or a little later), the so-called Hatcher Cargo. Salvaged in the early 1980s and auctioned in Amsterdam in portions between 1983 and 1985, this cargo, probably destined for Batavia, consisted of a huge variety of Kraak and Transitional porcelain (fig. 7), with a number of previously unknown types and decorations. Yixing and Zhangzhou ceramics were not present, but a small batch of Dehua porcelain was. As documentation, the Hatcher Cargo is like a time capsule that, among other things, makes it clear that in addition to the VOC’s official trade, there was a potentially more extensive private trade that certainly contributed to the assortment that could be purchased in the Netherlands.

Japanese porcelain

The shortage of Chinese porcelain made itself felt worldwide and led to two responses as far as the Netherlands and the VOC were concerned. In Delft, the pottery industry flourished with the production of imitations. Chinese decorations were copied in blue on the white tin glaze (faience) that completely covered the reddish or yellow earthenware, thus suggesting white porcelain, from which it could hardly be distinguished at a distance. The much lower price was, of course, also important for the client.

Since 1642 the VOC had maintained a trading station in Japan on Deshima, an artificial island in the Bay of Nagasaki. Some distance north of Nagasaki was Arita, where porcelain had been made for the domestic market since the early seventeenth century. With the cessation of production in China, Japanese porcelain became an alternative for the VOC, both for its inter-Asian trade and for the Netherlands. That Japan isolated itself at the time and did not conduct its own exports, leaving them to the VOC and Chinese traders, helped of course. From 1658 until the early 1680s, the Company bought porcelain from Arita every year. It was an immediate success in the Netherlands, mainly because of its bright decorations in overglaze enamel colours (FIG10), something new after the blue-and-white Kraak and Transitional porcelain of the preceding half-century. While Japanese Arita also has a lot of underglaze blue, the polychrome pieces made it exclusive. However, the limited supply also made it more expensive than Chinese porcelain.

Today in Western literature we distinguish between two main types of polychrome Japanese porcelain: Kakiemon and Imari. The former is named after a family of potters in Arita. Kakiemon is characterised by refined decorations in bright, soft enamel colours with plenty of space around the representations (fig. 8). The body is immaculately shaped and sometimes covered with a distinctive cream-white glaze. Imari ware, named after the export port outside Arita, features denser and more profuse decorations in a combination of underglaze blue, iron red and gold, sometimes with some additional enamel colours (fig. 9). This type in particular suited the Baroque style and was distributed from the Netherlands throughout Europe.

The popularity of Japanese porcelain in Europe made it profitable for the VOC, but it also stimulated its employees in Deshima to conduct extensive private trade. Chinese traders in Nagasaki also shipped Arita porcelain to China and sold it to Europeans there.

Kangxi porcelain

In China in the late seventeenth century, Emperor Kangxi (1662-1722), who had imposed his rule by force, allowed overseas trade to resume in the southern provinces from 1682. Porcelain producers in Jingdezhen immediately capitalised on this and offered an abundance of new, fashionable types. Unlike before, this range did not have to be ordered first, but Chinese junks brought it to Asian markets directly, including Batavia. The VOC took advantage of this and stopped buying Japanese porcelain for the Netherlands, also because the Chinese competed fiercely on price. A wide range of both blue-and-white and polychrome porcelains in a variety of shapes that appealed to Dutch/European tastes was thus available in Batavia.

Chinese potters had noticed that polychrome Japanese porcelain sold well and now offered several types, including the so-called famille verte, porcelain decorated in various shades of enamel colours, especially green. This type is often carefully and elaborately painted with plants, animals, landscapes and figural scenes, surrounded by complex border decorations (fig. 10). One variant is famille noire, with a black ground beneath a verte enamel decoration. In addition, a palette of monochrome enamels was developed: black, green, iron red, citrus yellow and celadon. As a reaction to Japanese Imari, Chinese Imari was produced with the same colour range, sometimes closely following the Japanese examples, more often with its own Chinese iconography. A separate category is the so-called Milk and Blood, decorated in iron red and gold, which was popular in Friesland and Groningen, but rare outside the Netherlands (fig. 11). Much export porcelain from the Kangxi period and later has a mark on the base, either a symbol, characters or an imperial mark usually denoting a Ming emperor, but also sometimes the emperor reigning at the time. Private traders increasingly discovered that not only the shape, but also the decoration could be produced as desired in Jingdezhen. It began with plates and saucers decorated with a family crest in underglaze blue for customers in Batavia, somewhat later also for families in the Netherlands (fig. 12). This ‘armorial ware’ gave rise to a fashionable trend of having all kinds of European representations depicted on porcelain, first in underglaze blue, later mainly in enamel colours. The VOC seldom ordered this chine de commande, so private merchants who could handle the small and exclusive runs took over the trade.

This private trade grew to such a degree in the years after 1685 that the VOC, less flexible in its logistics and less responsive to rapidly changing fashions in the Netherlands, began to suffer from the competition. Profits on the porcelain imported by the Company diminished, and in 1690 the Heren XVII, the directors of the VOC, decided to stop buying it for the Netherlands altogether. Private trade completely took over the supply of porcelain to the Netherlands, which means that almost all of the Kangxi porcelain in Dutch collections was not supplied by the VOC, but by private traders.

Also dating from this period is a documentary cargo of porcelain from two wrecked Chinese junks en route to Batavia: the Vung Tau and the Ca Mau. The first wreck dates from around 1690 and shows the extent to which the new fashion of drinking tea and coffee determined the assortment. There is a wide variety of cups (without ears) and saucers, as well as all kinds of sets of covered vases and beaker vases (garnitures) that had a decorative function in Dutch interiors. The Ca Mau can be dated around 1725. Both cargoes confirm that drinking utensils had become increasingly important, but also that more special pieces such as figurines, jugs, vases and even spoons were also considered saleable.

Trading on Canton

It was not until 1728 that the VOC once again became involved in sourcing porcelain, and this time in China itself. Around 1700, Canton (present-day Guangzhou) on the Pearl River in the southern province of Guangdong had developed as a centre for overseas trade. Western Companies bought their Chinese goods there, especially tea, which was starting to become the beverage of choice throughout Europe. Porcelain was an interesting by-product in this regard. For the VOC, Canton was initially of little value because all the Chinese merchandise, including tea, was brought to Batavia by junks. As the tea trade became more important, competition grew and freshness became a priority. Shipments of tea from Batavia to the Netherlands lagged behind, profits sank and eventually the Company decided to sail to China and fetch the fresh tea itself. It goes without saying that porcelain was also purchased. Packed in wooden crates and ‘bundles’, it served as a base layer in the ship’s hold and thus protected the crates of tea stored on top from moisture. One advantage was that the VOC was now no longer dependent on the Chinese junks, but could buy locally in Canton itself. As with tea and silk, orders for porcelain included detailed lists indicating the types, models, colour schemes and quantities desired, as well as the available budget. Three categories were distinguished: blue-white, enamelled (with overglaze enamel colours) and Chinese-Japanese, i.e., Chinese Imari. The polychrome-enamelled porcelain was almost always decorated in the so-called famille rose palette, a new type of enamel developed around 1720 with shades of pink-red that harmonised beautifully with other enamel colours (fig. 13). The choice of decoration was left to the clients and was almost always in Chinese style.

Chine de commande

The VOC seldom purchased porcelain with a European decoration, with the exception of ‘Pronk porcelain’, an experiment carried out between 1734 and 1741, in which the painter Cornelis Pronk (1691-1759) made designs for tableware and ornaments. These were to be decorated in China after the chinoiserie designs he had drawn, with the ‘Parasol Ladies’ being the most popular (fig. 14). The commissions were closely monitored by the producers in Jingdezhen, but the price was so steep that the Company soon stopped the orders. Private individuals latched on to this and all kinds of variants saw the light of day.

A lot of chine de commande porcelain was produced in the eighteenth century as part of the private trade. The decorations were copied by Chinese painters from prints – often French – accompanying the orders, and are very varied, ranging from religious to erotic scenes, from cityscapes to classical mythological images, from portraits to political events. Encre de chine (thin lines in black enamel) could be used to accurately copy the engravings from prints (fig. 15). Initially, commande was executed in underglaze blue in Jingdezhen, later also in overglaze enamel colours. However, as orders became more substantial, around 1740 it proved more convenient to apply the polychrome decorations in Canton itself and muffle fire them at a low temperature in local kilns. Moreover, the client could check in situ whether everything was to his liking. The production runs were small, it took a lot of effort to deliver an order to the client in Europe, and it was unprofitable for the VOC. But the status commande enjoyed was apparently enough to sustain this category until the end of the eighteenth century.

Utility ware

The VOC concentrated on porcelain utility wares for the Netherlands: plates, bowls, tableware, and coffee and tea ware. The more luxurious porcelains included spittoons, fruit baskets, punch bowls, garnitures, etc. Large quantities were involved annually: over 200,000 pieces could be loaded on each ship, and often as many as three or four VOC ships were docked in Canton at the same time. The porcelain cargo in each of the ships was worth approximately 35,000 to 40,000 guilders and comprised about 5% to 8% of the total value of the entire cargo. In the Netherlands, all this porcelain was auctioned in Amsterdam, Middelburg or one of the other cities where the VOC was based. The yields could vary greatly, but if a particular type of porcelain generated less than 40% profit, it was removed from the assortment.

Porcelain salvaged from the wreck of the Geldermalsen (1752) provides a splendid overview of an average cargo aboard a VOC ship (fig. 20). It was auctioned as the ‘Nanking Cargo’ at Christie’s in Amsterdam in 1986. A study collection at the Groninger Museum includes all the types and variants that were found and correspond with the preserved cargo list from China. Examples of the more exclusive pieces that were shipped privately are also included in this collection.

Plagued by the English wars, high operating costs and waning interest in Chinese porcelain, the VOC’s purchases declined in the late eighteenth century. Alternatives such as German and French porcelain or English pottery were more fashionable. In 1799, the VOC went bankrupt and although the Netherlands Trading Society (Nederlandsche Handel Maatschappij) continued trading with China and Japan after the French era, there was no longer a structured porcelain trade.

Literature

There are many publications on many aspects of export porcelain, but source editions based on VOC archival records are scarce.

For China and Japan in the seventeenth century, see among others:

Tijs Volker, Porcelain and the Dutch East India Company as recorded in the Daghregisters of Batavia Castle, those of Hirado and Deshima and other contemporary papers, 1602-1682, Leiden: E.J. Brill, 1954, 1971

Tijs Volker, The Japanese Porcelain Trade of the Dutch East India Company after 1683, Leiden: E.J. Brill, 1959

Cynthia Viallé, ‘The records of the VOC concerning the trade in Chinese and Japanese porcelain between 1634 and 1661’, Asian Art 22/3, 1992, pp. 6-34

Miki Sakuraba & Cynthia Viallé, Japanese Porcelains in the Trade Records of the Dutch East India Company, Fukuoka: Kyushu Sangyo University, 2009

For China in the eighteenth century:

C.J.A. Jörg, Pronk Porcelain. Porcelain after designs by Cornelis Pronk, exhibition catalogue Groninger Museum/Haags Gemeentemuseum 1980

C.J.A. Jörg, Porcelain and the Dutch China Trade, The Hague: M. Nijhof 1982