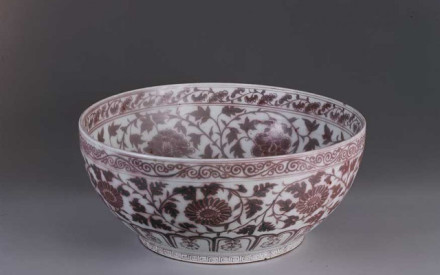

The sub-collection of Asian ceramics at the Groninger Museum (fig. 1) is one of the oldest in the overall collection. Since the founding of the museum in 1894, a number of substantial gifts and bequests from Groninger collectors have formed the foundations on which the Asian porcelain collection is based.

The interest in ceramics from areas such as China and Japan and in collecting these has existed for centuries in the city and province of Groningen. The museum reflects this interest, particularly with the large number of Chinese and Japanese export porcelains from the period of the Dutch East India Company (Vereenigde Oostindische Compagnie, VOC), which now form the most important and extensive part of the collection, totalling over 9,000 pieces.

In the second half of the nineteenth century, as a reaction to industrialisation and the mass production of consumer goods, Europe experienced a revival of interest in traditional crafts and, by extension, in Asian utility wares, particularly porcelain. Collections of such objects were established in the Netherlands, especially in the north, where there were ample financial resources. Mr Albertus Nap (1834-1918) and Mr Mello Backer (1807-1883), for instance, were very active collectors and also bought at auctions in Amsterdam and elsewhere. More locally formed were the collections of Johannes Antonius Wreesman (1866-1929), Anna Geertruida van Aldringa Wichers (1857-1904), the Arkema sisters, and Elisabeth Boerema-Takens (1849-1928). It was these and other private collections that formed the basis for the current museum collection. This collection, which already numbered about 5,000 pieces around 1920, is extremely varied and includes not only objects that are still considered international masterpieces, but also series of plates, cups and saucers that were previously part of the donors’ household effects.

The organisation and description of the collection is largely due to the efforts of curator Minke A. de Visser (1898-1966, working pro bono from 1921 to 1966). In enlarging and enriching the collection, she focused both on ceramics produced for the domestic market in China and Japan and on porcelain exported to the Netherlands. Her importance for the museum cannot be emphasised enough. In addition to her work with furniture, silver, textiles and glass, she was particularly interested in Asian ceramics. Although self-taught, she grew into an internationally respected specialist who gave the collection structure, a framework and depth. De Visser worked in close consultation with Nanne Ottema, founder of the Princessehof National Museum of Ceramics in Leeuwarden, whom she saw as her mentor, although Ottema acknowledged that her systematic and scientific approach, insight and professional knowledge, were superior to his own. She spent a great deal of time with Jan Menze van Diepen, a collector from Groningen, who was a mainstay of her career. She advised him on his collection and they bid and bought together at auctions and dealers. The Van Diepen Collection is now housed in the Fraeylemaborg in Slochteren.

After Minke de Visser passed away, Jenny M. Cochius was appointed her successor. She focused more on ceramics made for the domestic Japanese and Chinese markets, for example, the Japanese tea ceremony. She in turn was succeeded in 1977 by Christiaan Jörg, who maintained De Visser’s collection policy, with an emphasis on the exchanges between Asian and European ceramics in both shape and decoration. In addition, he focused more generally on export ceramics for the Western market. Porcelain from shipwrecks was a new and very interesting field, and a source of numerous new insights in dating and classifying the typology and decoration of this export porcelain. Groningen is the only museum that has a wide range of documented wreck finds such as, for example, of the VOC ship Geldermalsen (1752) (fig. 2-3), the Diana (1817), a ship that sailed under the English flag and of the Ca Mau, a Chinese junk that sank on its way to Indonesia (c. 1730). Despite his retirement in 2003, Jörg’s involvement with the museum has continued unabated. The collection is still growing, mainly due to his mediation, and his knowledge and insight are essential to making it more accessible, for example, through exhibitions and publications.

Today, the museum exhibits a varied overview of the various subgroups, such as Kakiemon porcelain from Japan, Chine de commande, Yixing and blue-and-white Kangxi ware (fig. 4-11). Kraak porcelain is well represented with almost all known shapes and types, there are some unique Transitional porcelain objects, and beautiful and important examples of famille verte and Japanese Imari as well (fig. 12-15). Also interesting is the sub-collection of Delftware with motifs and shapes inspired by Chinese and Japanese porcelain, an example of the way in which porcelain from these countries inspired local arts and crafts in the Netherlands.

Click here to visit the Groninger Museum’s website.